Buy Speedster and the Skunk

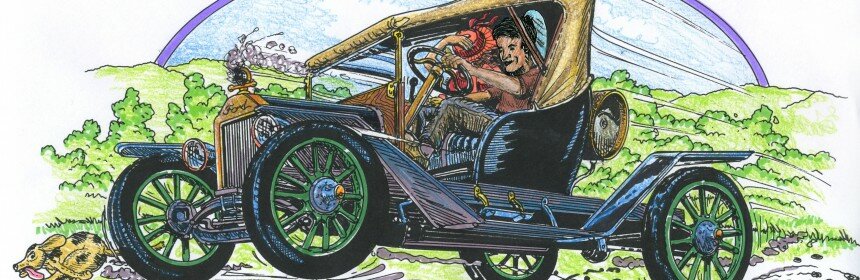

When I started writing I thought this would be a short story. When I was a boy my dad told me what I thought was a really interesting, funny, embarrassing true story. I asked to hear it until I’m sure he got tired of me asking. In a nutshell, when he was in high school in 1929 or ’30 he traded his pony for a 1912 Model T Ford touring car. With help from friends he converted it into an early hot rod called a Speedster. Before it was finished (no windshield, no top, no body really) he drove it to a dance. On the way home he tried to bluff a skunk and paid the price. Last fall I thought I should get it down on paper. My friend John Lingo, who has restored old Fords to showroom condition, read an early draft and helped make it more accurate. It grew. By the time it was done it was a novella, fifty-some pages long. It cried out for art. Jim Caswell, one of the best car artists I know, liked the idea and drew a cover and four more pen-and-ink illustrations. They still knock me out. Laura Ann Sorrell helped Jim with the people, and my old friend Earl Carter stitched the machines and people together in Photoshop.

It’s available on for Kindle readers (or iPad or iPhone) for $3.25. As soon as I can, I want to offer a print version too. Here’s the first chapter:

What Exactly Happened?

“Hey Tom Bragg! I hear you’re sleeping in the barn.” Bea stopped in the shade, swung her tennis racquet at the air and waited.

He laughed, but still felt sheepish as he crossed the street. “Not any more,” he said. “Bad news gets around, huh?”

Bea was one of the prettiest, nicest girls in his class, and a friend. A month ago he would have walked right up and offered to carry her books, or whatever. Now he stopped ten feet back. His sisters still said he had to stand back from people until further notice. Bea smiled. “You’re the talk of the town. How long has it been? More than a week.”

“Almost two,” he groaned. “I’m back on the upstairs porch though. Not the sleeping porch, the regular porch. On a cot.”

“Your poor mother.”

He hung his head. “I know. She’s been great, considering that she and Hattie and the girls had to start spring cleaning all over again. She still shakes her head, but she can smile now.”

Bea shook her head too, but she also almost smiled. It was a sympathetic smile.

“I learned one thing, at least,” he said. “If a skunk gets you, don’t go in the house. Sit on the curb and cry.”

Bea giggled. “I’ll try to remember. I really don’t smell anything.” She leaned forward with her racquet behind her back and sniffed the air. She was still an arms length away. “I really don’t. Somebody not very nice said you smelled like tomato juice poured on a dead skunk. You don’t though.”

“I did at first. It’s a whole bunch better. Plus I just took a shower.” She looked sympathetic. Without moving away she took a backhand swing, leaned forward and sniffed again.

“After-shave?”

He beamed. “And how! I’ve used almost a whole bottle in two weeks. Daddy says it’s an improvement.”

“It smells nice.”

Tom Bragg stood up a little straighter. “Really? You’re the first person to say that. Do you mean it?”

She nodded. “I like Old Spice. My Daddy uses it.”

He smiled. “I get to work at the drugstore Saturday. Dr. Westmoreland thinks I’ll be okay.”

“You’ll be fine. The drugstore smells like disinfectant anyway, and perfume. And vanilla. You’ll be behind the counter. It’ll be fine.”

“I hope so. I need money so I can get another radiator. I can’t get the smell out.”

“I’m sorry. I heard your cute car was wrecked.”

“I heard that too, but it’s not true. Ruined maybe, until the smell wears off, but not wrecked. I didn’t hit the skunk, or anything else.”

“What did happen?”

“It’s embarrassing. You don’t want to know.”

“Yes I do.” She smiled.

“How much time do you have?” Tom Bragg didn’t have much time himself, but couldn’t remember why just now. You can’t think when girls smile like that.

“Just enough.” Bea was exactly his height, and really pretty when she smiled. Her eyes sparkled. “Start at the beginning.”

Darn Impressive for a Boy

Tom Bragg wanted to drive his speedster to the dance. He wanted to show it off, and be seen in it. The speedster was still rough around the edges. It needed a few things, but it ran great and looked sharp.

At least it looked sharp to him, and to most of his friends. Rich boys had nicer cars, sure, but they had not built those cars themselves. Tom Bragg had built the speedster, with help from his friends. He snatched time after school, between band practice, gymnastics, his job at the drugstore, chores, studying, sleeping and eating. It had taken months, but it was a darn good car. Especially to have been built by a boy in high school. Even Daddy said so.

Of course, he hadn’t built it from nothing. It been manufactured on Henry Ford’s famous assembly line in 1913, right after Tom Bragg was born Dec. 7, 1912. Most seventeen-year-old cars are not as stylish as most seventeen-year-old-boys would like, but this one was as up-to-date as he and his friends—and his budget—had been able to make it. People who knew what they were looking at were impressed that a high school boy could accomplish so much. Even people who were not all that interested in cars noticed it. But in 1930, most everyone was at least a little excited about automobiles. Automobiles, aeroplanes, radios, Kodak cameras, talking pictures. New things, modern things.

Until Tom Bragg got hold of it, the speedster-in-waiting had spent most of its seventeen years looking like a grandmother’s car. It had rolled off the assembly line padded like a comfortable buggy, with a tall, brass-framed windshield and a cloth top that made it look a bit like a covered wagon about to cross the prairie.

Tom Bragg removed the big touring car body right away, and hauled most of it to the foundry. The scrap metal brought just enough money for a few key parts. Even better, the buggy-like body wasn’t sitting in the back yard looking tacky. Mother and Daddy were tolerant when Tom Bragg re-built that biplane back there, but this was just parts of an old car. When the body came off, the front fenders stayed, and he started looking for two more just like them. He wanted to mount them backwards, over the back wheels. Plenty of speedsters had bookend fenders like that, and it looked sharp. For now, the speedster-in-progress stood naked on its original twelve-spoke wheels and tires, pretty good ones, and it still had the original brass radiator. It still had the original black folding hood too, and the tiny black cowl and firewall that the Ford Motor Company had given it. But so did most speedsters.

Want to read more? Here’s the link. I’m still learning, so you may have to paste this into your address line.